Why Public Education In America Needs Its Own #MeToo Movement: School Shootings, Teacher Erasure…

Why Public Education In America Needs Its Own #MeToo Movement: School Shootings, Teacher Erasure, Toileting Pay, and an Inadequate Constitution

I’ve been thinking about this blog since late January and began writing it yesterday.

As I resume writing now, the shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida is still in a live shooter situation. The fear, worry, grief, confusion, and horror that everyone struggles to bear when shootings occur in our nation’s schools should never be part of our lives. This devastation should never be part of our children’s lives and school experiences.

Never.

But there are many victims in our education system in America. Victimization is not just due to the school violence that attacks our children’s physical, mental, emotional, and psychological safety and well-being every day. Victimization stems from other issues inherent in our system

School Shootings

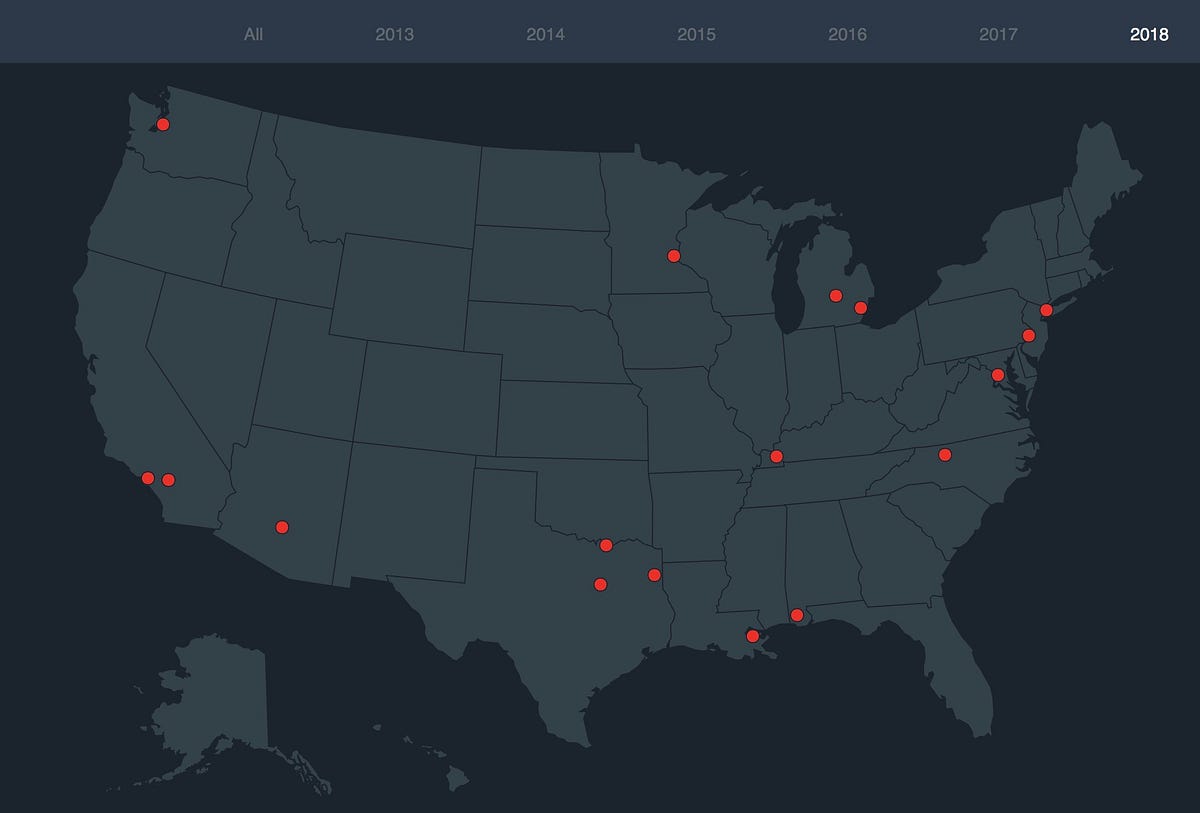

Over the past five years, there have been almost 300 school shootings in the United States (290 School Shootings in America Since 2013, 2018). 17 of these shootings occurred from January 1st to February 8th, 2018 alone. However, these statistics do not include the many more incidents of firearms that are brought into schools but not discharged, or of firearms that have been discharged off campus (290 School Shootings in America Since 2013, 2018). Every school shooting takes an immediate heavy toll on students, staff, schools, and our local and national communities, and has a long-term documented impact on emotional and psychological health, student enrollment in the affected communities, and even hinders students’ ability to learn efficiently (Beland & Kim, 2015; Juvonen, 2001; 290 School Shootings in America Since 2013, 2018).

Among all developed and developing countries in the world, America has the highest number of school shootings and school violence incidents per day. Today’s shooting in Parkland, Florida is the 18th in the country this year. From 2013 to 2017, school shootings in America occurred at the rate of about one per week. In 2018, we’ve had one school shooting every 2.5 days.

Every day, school shootings and school violence in America make our 55 million students (K-12 Facts, 2018) victims of our public education system. Due to shootings and violence in our nation’s schools, every day 55 million students in America cry #MeToo.

Today’s catastrophe is just unfolding, and the #MeToo cries scream.

Data Analytics & Teacher Erasure

In the U.S., K-12 education continues to evolve with a rapidly increasing infusion of technology-based data analytics. Simultaneously, teachers who make “hundreds of decisions each day” (Clark & Peterson, 1986; Danielson, 2016, p 19) continue to lament the increasing and time-consuming constriction of conflicting demands (Danielson, 2016), multiple systems to manage, lack of support, low pay and more. Today, “big data… promises a new salvation… Collect and analyze enough data [and] the state of education is going to improve” (Press, 2012, p. 1).

But collecting and analyzing increasing quantities of data within our schools, districts, states and nation, has not helped student outcomes in our nation to improve.

Learning analytics entered our schools to enable teachers and administrators to monitor the progress of students in their use of content, and their interactions and participation during courses so that early intervention could be done to aid course completion (Reyes, 2015). Silicon Valley, and our data-driven friends there, quickly transitioned the U.S. education system to predictive analytics and are now racing to prescriptive analytics. Predictive analytics take learning analytics up a notch and based on multiple measures, forecast students’ performance (Rethinam, 2014), with a focus on who might drop out. Then, educators are relied upon to determine and implement measures to curtail drop out and improve students’ academic outcomes. Prescriptive analytics is the newest wave. Here the systems collect, analyze, predict and prescribe the solutions so that technological systems control the entire show with less need for the teacher.

While educators have always been data workers (Olasrud, 2014) the increasing emphasis on the use of data analytics in K-12 education is both increasing the burdens on our teachers and undervaluing them. In both respects and as we erase the need for the teacher, we victimize the 3.1 million teachers (K-12 Facts, 2018) who work in our nation’s public schools.

Furthermore, schools, as microcosms of society, are the institutions where our young people are socialized into the citizens we want them to be. After families, teachers and school personnel hold this responsibility for society and citizenry. As we continue the current burdening, undermining and erasure of teachers, we eliminate the social-emotional-behavioral guidance and civics education that our children need.

And so, we victimize our own children further. That’s 55 million children, who every day, weep #MeToo.

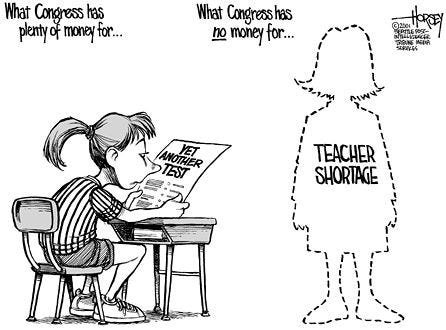

Toileting Teacher Pay and Flushing Education

Two-thirds of teachers in the U.S. feel undervalued in the business of education (Coughlan, 2014). Funding problems, 10–16 hour-long workdays for teachers, declining teacher salaries relative to inflation that puts many of them in the troughs of poverty (Murray, 2013; Myths and Facts About Educator Pay, n.d.), and mounting teacher turnover, mean we have bigger problems to face. Additionally, the growing propensity to treat education as a “business” only further complicates our K-12 education system difficulties.

According to Swan (2016), the observer effect of teachers is of greater importance than analytics. Soland (2013; 2014) too, states that teachers are excellent at identifying off-track students, so much so that their predictions of which students would become drop-outs edges out the data analytics and predictions of Early Warning Systems (EWS) by 1%. Teachers process countless pieces of data every moment of the day, and on the basis of this real-time data analysis make formative assessment decisions that result in the immediate, short- and long-term adjustments to instruction to meet students’ needs. They also counsel students, call parents, share concerns, submit referrals for RTI, and provide other supports.

In the real world of a still socially constructed education system, we maintain the need for human beings who serve as teachers, whose brains are effective analytical and processing systems, whose hearts love, and whose spirits propel the sacrifice of much for the sake of our children’s futures. When we fail to pay our teachers a living wage, we force them to run to second and third jobs, which knives through the off-the-clock hours they need to put in to do their jobs effectively and highly effectively. When we shortchange our teachers, without whom education is impossible, we victimize them and their students. 20–70% of newly certified American teachers quit within five years (Donaldson & Moore Johnson, 2011; Goldring, Taie, & Minsun, 2014) chiefly because of heavy workload and low salary.

Can we afford to #MeToo our 3.1 million educators and 55 million children in public schools?

No.

In 2012, the education system in the United States, the country generally known as the greatest and most powerful country in the world, was ranked 17th out of 40 countries in the world (Lurie, 2013; The Learning Curve, 2012). Despite reform after educational reform, academically, as a nation, we continue to fail compared to our counterparts. According to the Program of International Student Assessment (PISA) which compares educational attainment of students every few years in countries across the globe, the U.S. continues to lose ground. In 2012, PISA results ranked the U.S. below Finland, various European nations, Asian countries taking 2nd to 5th place, Canada and Australia (Lurie, 2013; The Learning Curve, 2012). By 2015, the U.S. ranked 31st among the 35 Organization for Economic Cooperation Development (OECD) industrialized member nations (Barshay, 2016), putting the U.S. in the bottom 11.4% of these nations.

Despite our declaration that we cannot afford the losses for teachers and students, we rob them every day. And every day their lament is one of #MeToo.

An Inadequate Constitution

In the U.S., education is not a constitutional right for all citizens (Lurie, 2013). The industrialized nations that outperform the U.S. every three years when the PISA is administered to 15-year-olds, all have education written into their national laws as a statutory right for citizens until adulthood (Lurie, 2013). These nations honor education for all through “constitutional guarantee” or “through an independent statute” (Lurie, 2013, para. 4).

The U.S. holds education to be the responsibility of the state government of each of its fifty states. As a result, the national or federal government funds only about 13% of public education and state and local governments provide the rest, having though to comply with strict regulations and conditions governing the shrinking federal funds received (Hanna, 2014). Schools and districts then have to make decisions about where to spend less. When cuts occur, as they often do, in areas of safety and security and maintenance, our staff and students are punished even more.

Historically too, states have designed their own standards to govern what students are expected to learn, and divvy up their states into districts, which then make and implement their own district regulations, budgets, and systems. What this means is that states have had to (and still do) vie against each other for federal funds, as in the 2009 Race to the Top funds (Ravitch, 2016). Within states, districts compete with each other for monies and grants, and as federal funding continues to shrink, the greedy, political, money-making business that education is becomes a raging war.

What we need is a constitutional amendment that makes education a statutory right for all K-12 citizens and takes back the existing privatized structure of education in the U.S. Such an amendment would remove the “business” out of education, and put all states and school districts on an equal playing field. This would enable the standardization of curriculum, and “the cultural assumptions and values surrounding [our] education system” (Lurie, 2013, para. 2), which is where we need to begin. A constitutional amendment would force government to fund the property rights to education for all children by placing its importance as high as the wall our current administration wants to build along the border where Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California, meet Mexico.

PostScript

This topic of why education in America needs its own #MeToo Movement involves much more. The problem is too multifaceted to address in one blog. Ten or twenty will likely not do it justice either.

At this moment, we know that 17 people tragically lost their lives in this afternoon’s shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, in Florida. Others are still fighting for their lives in the hospital. Many more will be scarred for who knows how long. The devastation will be felt most at the site and in the communities in the immediate vicinity of the school. But heartbreak and grief are already rippling out to the entire nation. Peel everything away and at the end of the day, all we have is our humanity, our lives, and each other. When will we, our politicians, and our government put an end to school violence and school shootings? When will we guarantee that going to school in the morning means going home at the end of the day? When will we ensure that teachers in all states can survive on their incomes and not have to hold second and third jobs? When will we safeguard our children’s rights to education?

When will #MeToo in education become a victory cry of a future offering possibility and promise in career, college and beyond?

References

Barshay, J. (2016, December 6). U.S. now ranks near the bottom among 35 industrialized nations in math. The Hechinger Report. Retrieved from http://hechingerreport.org/u-s-now-ranks-near-bottom-among-35-industrialized-nations-math/

Beland, L. & Kim, D. (2015). The effect of high school shootings on schools and student performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 201X(XX), 1–14. doi:10.3102/0162373715590683

Budget of the U. S. Government: A New Foundation for American Greatness: Fiscal Year 2018 (2017). Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved 2017, June 1, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/budget.pdf?inf_contact_key=785fc6fe2bec904ff877c5e8235f7396b019714453ba7d0c254ebb0dc6c0ff811

Clark, C. M., & Peterson, P. L. (1986). Teachers’ thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (ed.), Handbook of research on teaching, 3rd ed. (pp. 255–296). New York: Macmillan.

Coughlan, S. (2014, June 25). Two-thirds of teachers feel undervalued, says OECD study. BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/business-27985795

Danielson, C. (2016). The working lives of educators: Creating communities of practice. Educational Leadership, 73(8), 18–23. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/may16/vol73/num08/Creating-Communities-of-Practice.aspx

Donaldson, M. & Moore Johnson, S. (2011, October 4). TFA Teachers: How long do they teach? Why do they leave? Education Week. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2011/10/04/kappan_donaldson.html

Goldring, R., Taie, S., & Minsun, R. (2014, September). Teacher attrition and mobility: Results from the 2012–13 teacher follow-up survey: First look. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014077.pdf

Hanna, R. (2014). Seeing beyond silos: How state education agencies spend federal education dollars and why. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED561101.pdf

Juvonen, Jaana. (2001). School violence: Prevalence, Fears, and Prevention. Rand Corporation, 1–8. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/issue_papers/IP219.html

K-12 Facts. (2018). Center for Education Reform (CER). Retrieved from https://www.edreform.com/2012/04/k-12-facts/#enrollment

Lurie, S. (2013, October 16). Why doesn’t the constitution guarantee the right to education?. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2013/10/why-doesnt-the-constitution-guarantee-the-right-to-education/280583/

Murray, C. (2013, August 5). How many hours do educators actually work? Ed Tech. Retrieved from https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2013/08/how-many-hours-do- educators-actually-work

Myths and Facts About Educator Pay. (n.d.). National Education Association (NEA). Retrieved 2017, December 3, from http://www.nea.org/home/12661.htm

Olavsrud, T. (2014, July 28). Can data analytics make teachers better educators? CIO. Retrieved from https://www.cio.com/article/2458056/data-analytics/can-data-analytics-make-teachers-better-educators.html

Press, G. (2012, September 12). Fixing education with big data: Turning teachers into scientists? Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/gilpress/2012/09/12/fixing-education-with-big-data-turning-teachers-into-data-scientists/#f4b67923c6d3

Ravitch, D. (2016, July 23). The Common Core costs billions and hurts students. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/24/opinion/sunday/the- common-core-costs-billions-and-hurts-students.html

Rethinam, V. (2014, June 12). Predictive analytics in K-12: Advantages, limitations & implementation. The Journal. Retrieved from https://thejournal.com/articles/2014/06/12/predictive-analytics-in-k-12-advantages-limitations-implementation.aspx

Reyes, J. A. (2015). The skinny on big data in education: Learning analytics simplified. Techtrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 59(2), 75–80. doi:10.1007/s11528–015–0842–1

Swan, K. (2016). Learning analytics and the shape of things to come. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 17(3), 5–12. Retrieved from EBSCOHost Database.

The Learning Curve: Lessons in Country, Performance in Education Report. (2012). Pearson. Retrieved from http://thelearningcurve.pearson.com/reports/the-learning-curve-report-2012

290 School Shootings in America Since 2013. (2018, February 8). Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. Retrieved from https://everytownresearch.org/school-shootings///